Cabbage may cut cancer risk

Printed from ABQjournal.com, a service of the Albuquerque Journal

Monday, November 28, 2005

Cabbage May Cut Cancer Risk

By Jackie Jadrnak

Journal Staff Writer

Dr. Dorothy Rybaczyk Pathak remembers, growing up in rural Poland, how her cousin would fetch a chunk of sauerkraut, frozen in a barrel stored in the barn through the icy winters. Little did she imagine then that the thawed side dish, served about five times a week with a little oil and sugar added, might protect her from breast cancer.

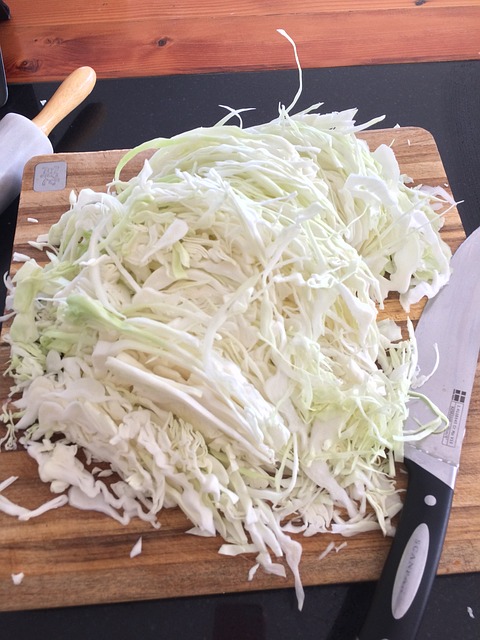

But now, as a professor of epidemiology with joint appointments at Michigan State University and the University of New Mexico, she has done a study that suggests that might be the case. Polish immigrants in the United States who ate a lot of cabbage when they were 12 or 13 years old— more than three servings a week— had a breast cancer risk about 70 percent lower than those who ate little cabbage during their adolescence and adulthood, she found. And the preparation of the vegetable made a difference. "Make sure it's raw or short-cooked," Pathak said, explaining that long cooking depletes the helpful substances. She presented the findings at an Oct. 30-Nov. 2 conference of the American Association of Cancer Research in Baltimore.

"When we think about increasing our risk (for cancer), we like to attribute it to the risk factors we are acquiring. But probably the risk is increased from both ends," Pathak said.

"The void when we remove from our diets food that protects us may be filled by foods that increase the risk of breast cancer ... It's not just what we acquire, but what we give up."

Pathak said she got interested in studying the question after noticing women in Poland have about one-third the rate of breast cancer as women in the United States. But when they migrate to the United States, or to other countries, their cancer rates soon rise to the same level as that of their new home. "So what is it that could be changing so rapidly?" Pathak wondered. "My primary hypothesis is that it was dietary."

In the 1980s, there had been an explosion of research showing anti-cancer properties of cruciferous vegetables: cabbage, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, for example. Research in cell lines and animal models showed those vegetables yielded compounds that could block cancer at early stages. The compounds activate genes that regulate enzymes that detoxify certain cancer-causing substances; that aid in DNA repair; that affect proliferation of cells; and that program death of damaged cells, she said. In animals, the compounds— glucosinolates and their breakdown products— help prevent cancer from forming in the first place, and also decrease the number and size of tumors once they form, she said. With that in mind, she noted that a person in Poland eats 30 pounds of cabbage a year, compared to an average of 10 pounds in this country.

Could that make a difference in breast cancer rates? While at Michigan State, she and colleagues took a look at Polish immigrants in the Detroit and Chicago areas— more than 400 all together, 140 of whom had breast cancer. They adjusted for any other differences in the groups that might influence cancer rates, such as reproductive history and exercise levels. And they asked about cabbage consumption, both as adolescents and adults, as well as whether it was eaten raw, short-cooked or long-cooked. Teens, eat your cabbage. Results showed lower cancer rates in women who ate lots of cabbage during their early teens. It's thought, Pathak said, that many of the cellular changes that lead to cancer might occur from the time a woman's breasts first start developing to the time of her first pregnancy.

There also was some risk reduction for women who ate moderate amounts (one-and-a-half to three servings a week) in their youth, but move to high consumption in adulthood. That protection didn't hold, though, for people who ate cabbage cooked a long time in stews, for example. Pathak, who came to the U.S. as a 16-year-old in 1964, confesses that she didn't eat cabbage regularly after she moved here. Her habits reverted after the study, she said. "I definitely started to eat more," she said, adding that her husband chops up cabbage for cole slaw and her daughter carries it to school in her lunch. "I asked my sister in Poland to send me the recipe for making my own sauerkraut. I would like to make my own," she said.

Pathak is following up this study with research to see if the presence of certain genes— ones that result in slower breakdown of protective substances, but also result in the body eliminating cancerous compounds more slowly— make a difference in how much protection a person can get from cruciferous vegetables such as cabbage. "There's so much gene-environment interaction," she said, noting that's the wave of future cancer research.

E-MAIL Journal Staff Writer Jackie Jadrnak

All content copyright © ABQJournal.com and Albuquerque Journal and may not be republished without permission. Requests for permission to republish, or to copy and distribute must be obtained at the the Albuquerque Publishing Co. Library, 505-823-3492.